Total global debt is set to hit a record $277trln by the end of 2020 according to the IIF. They reported that the debt had already ballooned by $15trln this year to $272trln through September. Governments, mainly from developed markets, accounted for nearly half. The developed markets’ debt to GDP overall has jumped to 432% in Q3 2020 up from a ratio of about 380% at the end of 2019. Emerging market debt-to-GDP hit nearly 250% in Q3 led by China with 335%. These are levels you can’t earn your way out of. You can default outright, or you can enter the path of least resistance and debase your currency and keep rolling the debt.

The bad news: debasement is baked into the cake this decade…

The good news: History is full of useful examples of how this tends to play out so investors can establish strategies that provide protection and even harness these strong forces…

In search of a thought framework…

The problem with using history as a guide on currency debasement is that the mind jumps to the extremes, the spectacular – say Weimar Germany or Zimbabwe – these examples seems so far removed from the perceived realities in developed economies today. When you read Adam Fergusson’s seminal book on the subject; ‘When money dies – The nightmare of deficit spending, devaluation & hyperinflation in Weimar Germany’ paragraphs like the following etches itself in your mind; “In war, boots; in flight, a place in a boat or a seat on a lorry may be the most vital thing in the world, more desirable than untold millions. In hyperinflation, a kilo of potatoes was worth, to some, more than the family silver; a side of pork more than the grand piano. A prostitute in the family was better than an infant corpse; theft was preferable to starvation; warmth was finer than honor, clothing more essential than democracy, food more needed than freedom.” Yet it seems farfetched and like something that only happens to other people, in places far away or back in time. In truth the debasement risk that confronts most investors today is of a more slow and insidious kind.

The kind of inflation (debasement by another name) we have seen so far this decade has mainly led to the warm feeling found at the center of the herd on a cold winter day, as the efforts of the main central banks has led to asset price inflation. But some investors, have at various intervals over the last decade, sobered up briefly from the spiked FOMO Cool-Aid to face the nagging question; Has this intoxicating ‘warmth’ not got some of the characteristics of peeing your pants to stay warm?

Maybe our debasement experience will be more akin to a dog left in a hot car on a midsummer day as opposed to that of the lobster dropped directly into a boiling inferno. Dehydration through heat exhaustion is a slower but equally lethal force, it leads initially to loss of strength and stamina before delirium gradually takes over as the system shuts down. Looking around global markets today there are signs of delirium.

With debt and deficit levels at historic highs and the beast of deflation at the gate with no real way out, it may be more instructive to take a look at some of history’s examples that does not involve wheelbarrows full of Reichsmark. Ideally, we can glean some lessons on what to expect on the path ahead and find some ways for investors to protect themselves and perhaps even harness these powerful forces underway for gain.

No country for old men…French history lessons…

For a telling overview of the unfolding dynamics when a nation chooses the “easy” path out of a debt trap, let’s commence with a segment from the illuminating and transcendent book; ‘Fiat Money Inflation in France’ by Andrew D. White, first published in 1896, yet eerily relevant today;

“First, in the economic department from the early reluctant and careful issues of paper we saw, as an immediate result, improvement and activity in business. Then arose the clamor for more paper money. At first, new issues were made with great difficulty; but the dyke once broken, the current of irredeemable currency poured through; and the breach thus enlarging, this currency was soon swollen beyond control. It was urged on by speculators for a rise in values; by demagogues who persuaded the mob that a nation, by its simple fiat, could stamp real value to any amount upon valueless objects. As a natural consequence a great debtors class grew rapidly, and this class gave its influence to depreciate more and more the currency in which its debts were to be paid. The government now began and continued by spasms to grind out still more paper; commerce was at first stimulated by the difference in exchange; but this cause soon ceased to operate, and commerce, having been stimulated unhealthfully, wasted away.

Manufactures at first received a great impulse; but before long this overproduction and over-stimulus proved as fatal to them as to commerce. From time to time there was a revival of hope caused by an apparent revival of business, but this revival was at last seen to be caused more and more by the desire of far-seeing and cunning men of affairs to exchange paper money for objects of permanent value. As to the people at large, the classes living on fixed incomes and small salaries felt the pressure first, as soon as the purchasing power of their fixed incomes was reduced. Soon the great class living on wages felt it even more sadly. Prices of the necessities of life increased, merchants were obliged to increase them, not only to cover depreciation of their merchandise, but to also cover their risk of loss from fluctuation and while the prices of products thus rose, wages, which had at first gone up, under the great stimulus, lagged behind. Under the universal doubt and discouragement, commerce and manufactures were checked or destroyed. As a consequence the demand for labor was diminished, laboring men were thrown out of employment and under the operation of the simplest law of supply and demand, the price of labor – the daily wages of the laboring class – went down until, at a time when prices of food, clothing and various articles of consumption were enormous, wages were nearly as low as at the time preceding the first issue of irredeemable currency. The mercantile classes at first thought themselves exempt from the general misfortune. They were delighted at the apparent advance in the value of the goods upon their shelves. But they soon found that, as they increased prices to cover the inflation of currency and the risk from fluctuation and uncertainty, purchases became less in amount and payments less sure, a feeling of insecurity spread throughout the country, enterprise was deadend and stagnation followed.

New issues of paper were then clamored for as more drams are demanded by a drunkard. New issues only increased the evil, capitalists were all the more reluctant to embark their money on such a sea of doubt. Workmen of all sorts were more and more thrown out of employment. Issue after issue of currency came, but no relief resulted save a momentary stimulus, which aggravated the disease. The most ingenious evasions of natural laws in finance which the subtle theorists could contrive were tried – all in vain, the most brilliant substitutes for the laws were tried, “self-regulating schemes, “interconverting” schemes – all equally vain. All thoughtful men had lost confidence. All men were waiting, stagnation became worse and worse. At last came the collapse and then a return, by a fearful shock, to a state of things which presented something like certainty of remuneration to capital and labor. Then and not till then, came the beginning of a new era of prosperity.”

Much of this is true today. It’s noteworthy that it is not just the nations currency that gets debased, but it is the entire financial and economic systems as well as society itself. The risk is not just a currency based one, it is pervasive. Liaquat Ahamed writes in his excellent book; ‘The lords of finance; 1929, the great depression and the bankers who broke the world’; “Monetary policy does not work like a scalpel but more like a sledgehammer.” This is another self-evident truth that investors would be prudent to heed.

The debt and deficit levels today were last seen in the immediate aftermath of WWII, so let’s again hit the French history books for some insights from the period leading up to that time.

In a BIS study of debt in the interwar years they ask the question; Who effectively paid the public debt? Here they look at the situation in France; “What factors helped bring down debt during the interwar? In the absence of German repatriations, successive French governments adopted various approaches to bring down the country’s large stock of public debt. Foreign debts were rolled over until the Great Depression and the advent of WWII diverted international attention. Governments also made short-lived attempts to implement restrictive budget policies and generate fiscal surpluses and used off-balance-sheet financing to obfuscate the true extent of the debt. Finally, fiscal dominance was used as a means to inflate away the debt.” My grandmother always used to say; “there is nothing new under the sun” – as with most things it would appear she was correct.

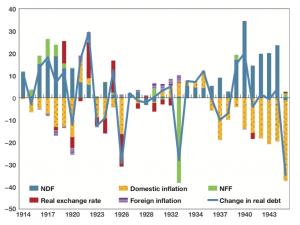

Here is a visualization of France’s interwar journey…

The decomposition of changes in France’s real debt by financing sources (1914-45 – Index).

Source: BIS Notes: NDF/NFF = Net domestic/foreign financing.

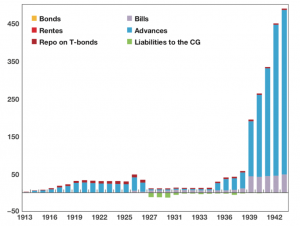

Central bankers to the “rescue”…

Banque de France’s net claims on the Government (1913-45) in French Franc Billions.

Source: BIS.

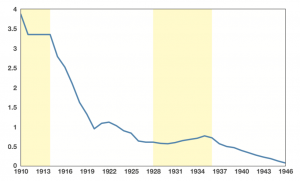

A journey down the (de)basement…

Purchasing power of the Franc (1910-46) in 2015 Euros.

Source: BIS/INSEE website. Notes: Purchasing power of the franc in terms of 2015 euro, accounting for inflation. Shaded areas represent periods of adherence to the gold standard.

Best be prepared for an all-weather type of journey ahead…

In times of change it is crucial to observe the lessons from the long arch of history and not get caught up in the short-term noise. The signals are all around us and the discerning investor should take note. A storm is coming, overindebted governments are likely to hide in the (de)basement. In times like these some investors seek shelter, others build windmills to harness these powerful forces. NN Taleb stated that; “The fragile wants tranquility, the antifragile grows from disorder, and the robust doesn’t care. Debt always fragilizes economic systems.”

Disclaimer

This piece (Strategic Thoughts) does not constitute an offer to sell, solicit, or recommend any security or other product or service by Strategic Capital Advisors or any other third party regardless of whether such security, product or service is referenced. Furthermore, nothing in this piece is intended to provide tax, legal, or investment advice nor should it be construed as a recommendation to buy, sell, or hold any investment or security or to engage in any investment strategy or transaction.